Hello friends! Here’s my monthly take on five most interesting developments in transport energy trends. What I try to do each month is select stories, studies and other interesting items that you may not have seen elsewhere but that really represents an important issue or trend that I think you would want to know about. Or I try to poke behind the hype to provide a deeper understanding of what’s happening. Items I selected this month include:

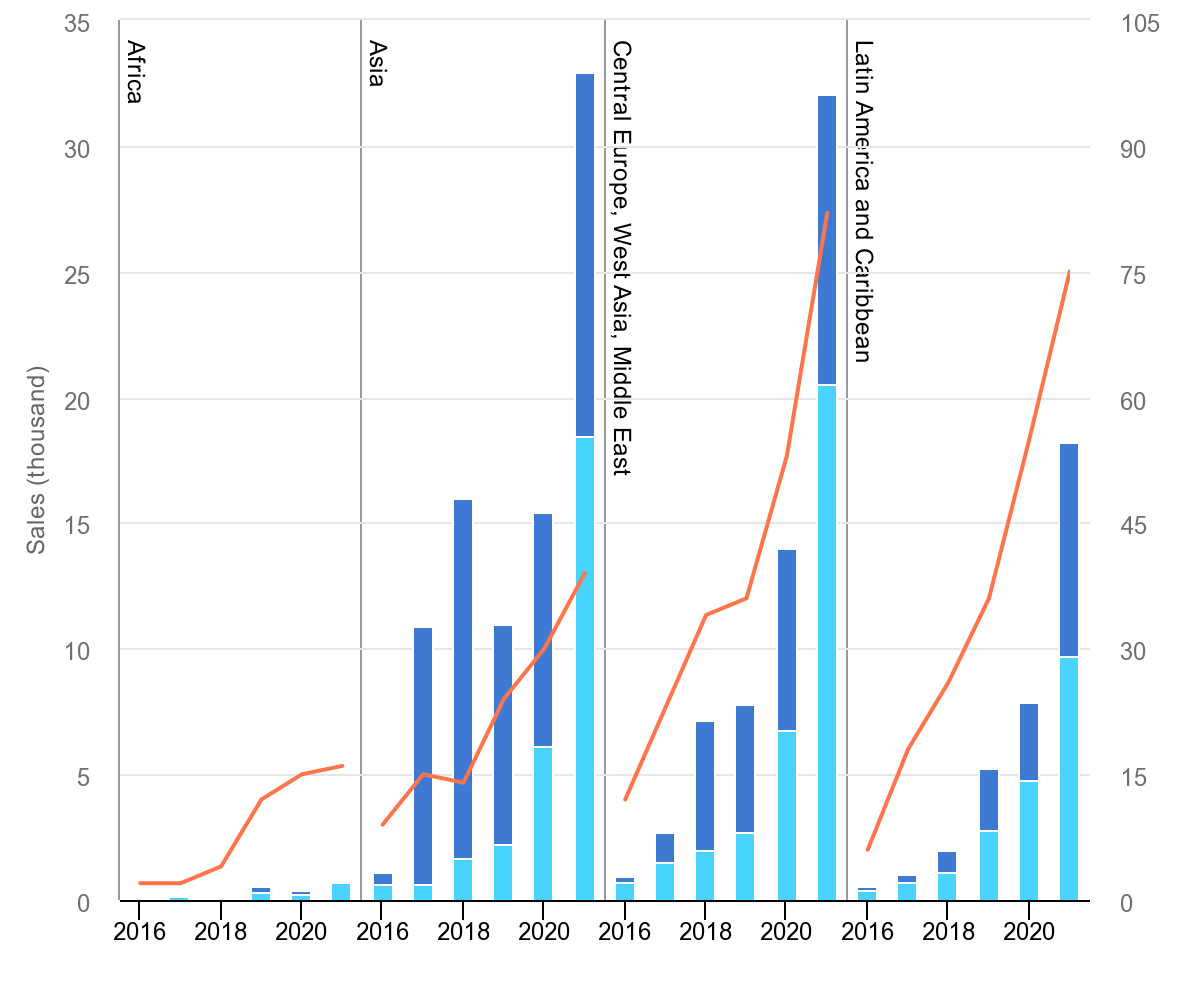

S&P Global: Global Electric Vehicle Sales Doubled; US Made EV Comeback in 2021 – S&P highlights IEA’s annual Global EV Outlook, noting China’s continued dominance. A record 3.3 million EVs were sold there in 2021, while the U.S. ended a two-year slump to see EV sales double, according to newly released data. In Europe, 2.3 million EVs were sold. Worldwide EV sales doubled year over year in 2021 to 6.6 million, and the EU and China represented 85% of sales. I dug in a bit to pull this chart from the report that summarizes sales and models available by region, 2016-2021.

Source: IEA, May 2022

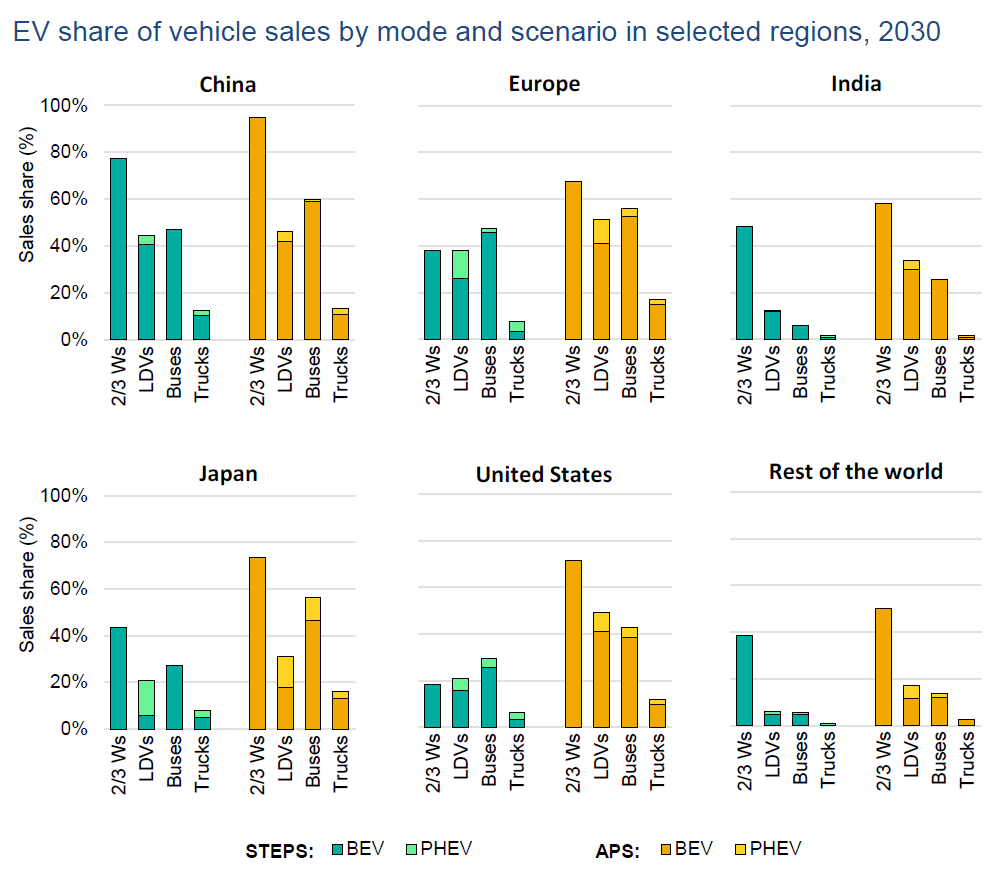

IEA projects China to continue leading in sales through 2030, as the following chart shows. I think, given our current economic and geopolitical environment, that the STEPS scenario (stated policies that are in place today) is probably more realistic. This means the U.S. sales share would be about 20%. (Coincidentally, that matches my own recent projection for the U.S.) China and the EU are at or over 40%.

[Notes: STEPS = Stated Policies Scenario; APS = Announced Pledges Scenario; 2/3Ws = two/three-wheelers; LDVs = light-duty vehicles; BEV = battery electric vehicle; PHEV = plugin hybrid electric vehicle. The countries included in Europe are listed in the Annex. Regional projected EV sales and sales shares data can be interactively explored via the Global EV Data Explorer on the IEA website. Source: IEA, May 2022]

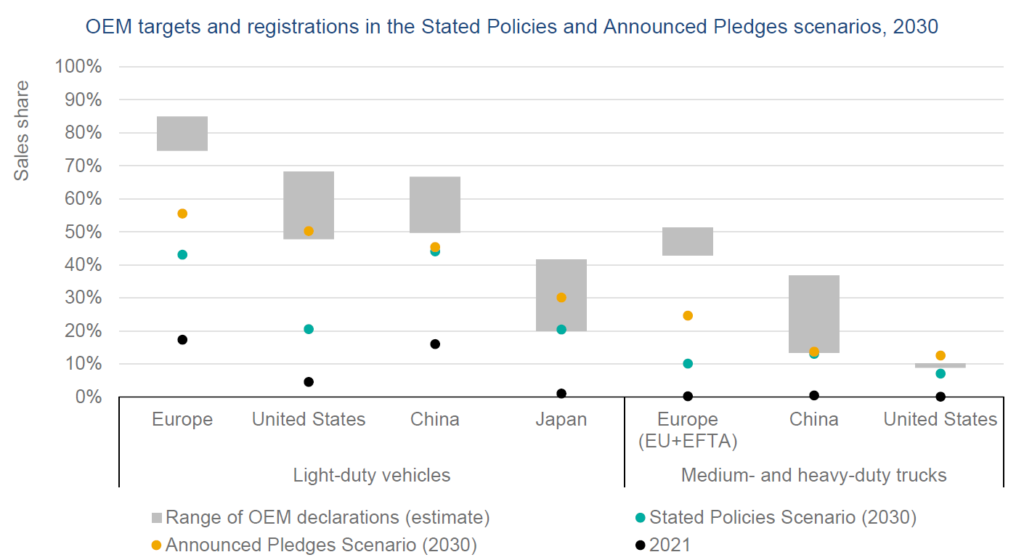

[Notes: OEM = original equipment manufacturer. For medium- and heavy-duty trucks, OEM pledges cover the European Union (EU) and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) whose members are Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. The figure compares OEM targets for HDVs (which, for some OEMs, include buses) relative to our projections for zero emissions medium- and heavy-duty truck sales (including fuel cell electric vehicles). Since annual sales of trucks substantially outnumber sales of buses, achieving HDV targets will require making and selling zero emissions trucks, which currently is a more challenging prospect than selling electric buses. The regional average market share in 2030 is calculated by collating announcements that explicitly mention ZEV market shares or ZEV sales by the top-15 OEMs in each region. Electric bus and truck registrations and stock data can be interactively explored via the Global EV Data Explorer. Sources: IEA analysis based on country submissions, complemented by ACEA; EAFO; EV Volumes.]

You may point the finger at governments for the myopic focus on “zero emission vehicles” and electrification as a singular decarbonization strategy, but it is the auto industry that far and away has made the most ambitious of plans. Some examples:

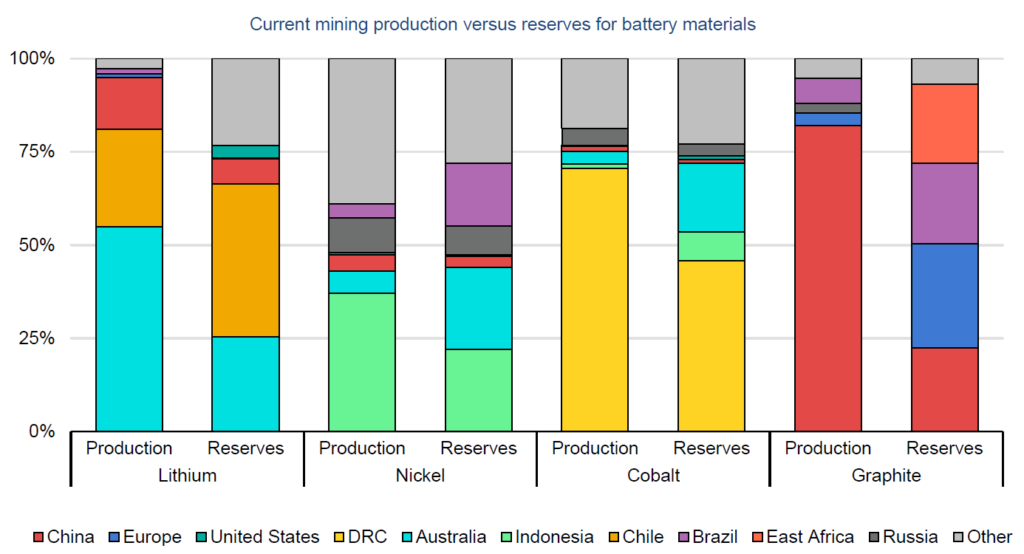

Another interesting aspect of the Outlook is the issue of minerals and rare earths. It’s been well publicized (in this column and in the wider media) that China dominates the entire EV battery supply chain. That’s no secret. But what about developing other sources? The figure below summarizes both current production and reserves.

]Notes: Li = lithium; Ni = nickel; Co = cobalt; Gr = graphite; DRC = Democratic Republic of Congo. Reserves refer to economically extractable resource as defined and determined by the US Geological Survey. Sources: IEA analysis based on US Geological Survey (2022).]

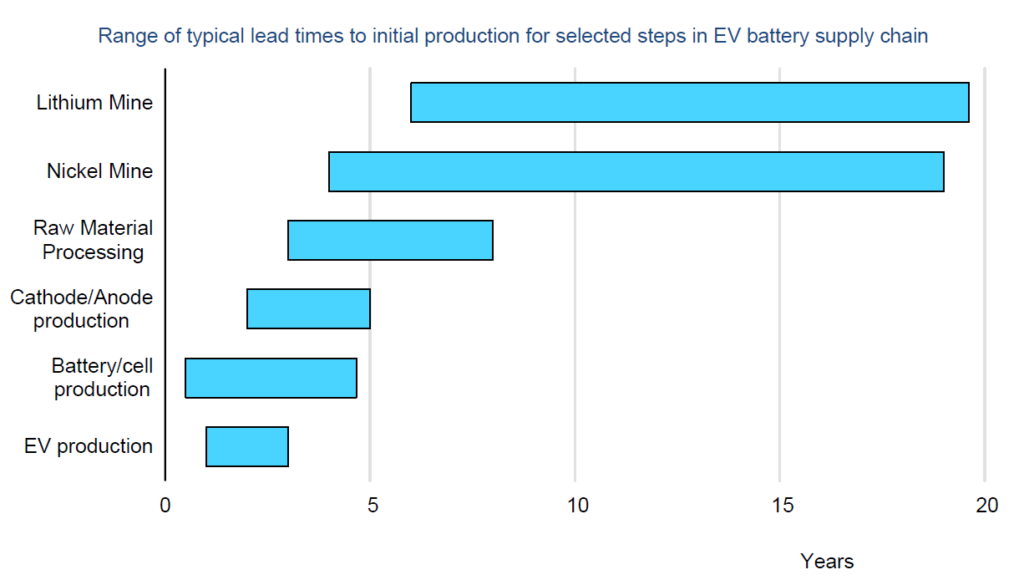

However, an eye-opening fact that I don’t think gets out there is the lead time in developing new sources. Check out the figure below. Developing a new lithium mine could take at the least 7 years and at the most 20. A similar timeline exists for nickel. As the article later in this post notes, mining companies are not exactly jumping to invest. It does have me wondering whether the supply situation is going to look like in a few years and how that might affect battery development and costs, and in turn, EV costs.

[Notes: Lead times for mines are calculated from completion of the preliminary feasibility study to the start of production. For other elements, lead times are calculated from investment decision to production. Sources: IEA analysis based on Heijlen et al. (2021); Benchmark Mineral Intelligence; S&P Global.]

As you might imagine, neither the French nor the German car industries are collectively and terribly enthused. A representative from the French automaker trade group PFA noted concerns over whether the sufficient charging infrastructure would be available as well as whether there would be enough buyers. These echo concerns voiced by ACEA. The German automaker trade group VDA minced no words: “The EU Parliament has today taken a decision against citizens, against the market, against innovation and against modern technologies,” said Hildegard Müller, president of VDA.

My direct professional experience is that bans can be tricky and can backfire. Case in point: State MTBE bans and an attempted federal ban in the U.S. in the early 2000s. Technology preferencing by policymakers can backfire as well. Case in point: Dieselization in the EU. Who created policies to foster diesel vehicles in the name of CO2 reduction in the 1990s? That would be the very same policymaking bodies set to ban the internal combustion engine now.

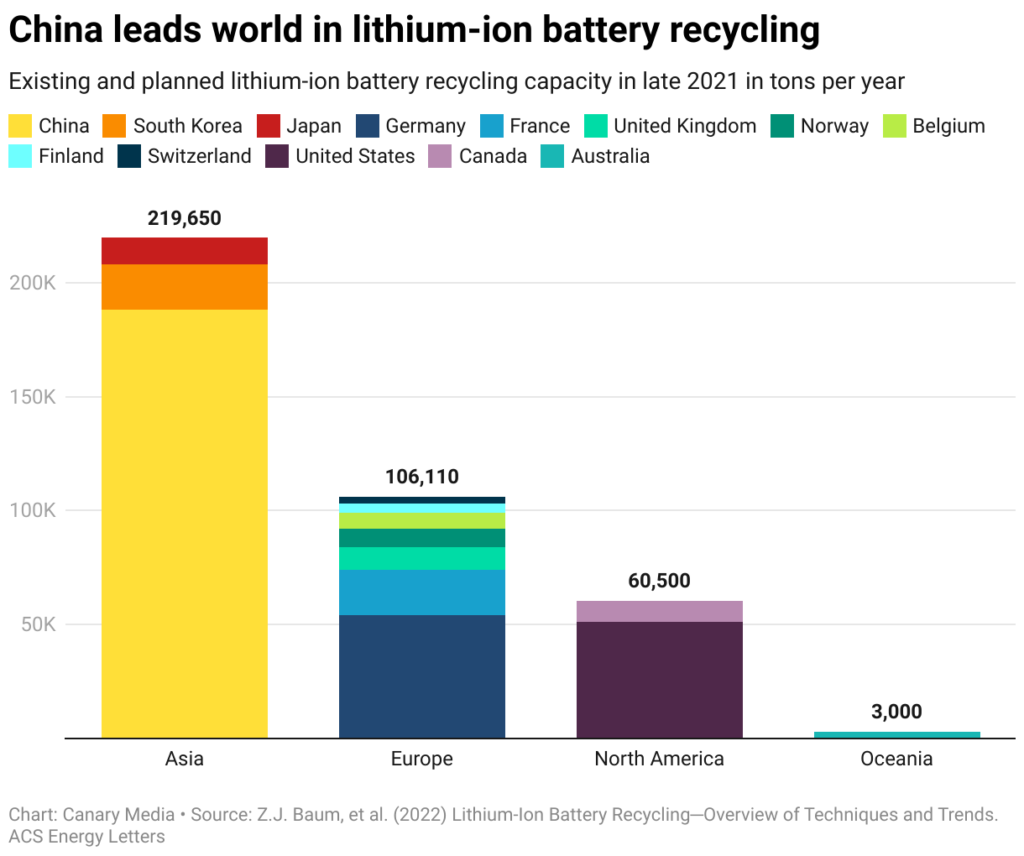

Canary Media: Chart: China Is Trouncing the US on Battery Recycling – This post notes that China is the global leader in recycling of lithium-ion batteries, far outpacing all other nations. As of late 2021, China had more than three times as much existing and planned lithium-ion battery recycling capacity as the U.S., according to a recent paper.

The post notes that in the U.S., lithium-ion battery recycling is a nascent industry, but starting to develop though policies to support the industry are barely being discussed at either the state or federal levels. In the EU, however, landfilling of batteries has been banned since 2006, and the Commission will be implementing new rules to make auto manufacturers responsible for recycling old batteries from their EVs, require new lithium-ion batteries to contain certain amounts of recycled content, and require new batteries to be designed in ways that make them easier to recycle.

China too has rules that have spurred the creation of its lithium-ion battery recycling sector. The country began promoting lithium-ion battery recycling through policy in 2012 and has adopted more measures since, including one in 2018 that requires manufacturers to collaborate with recycling companies to improve the recycling process.

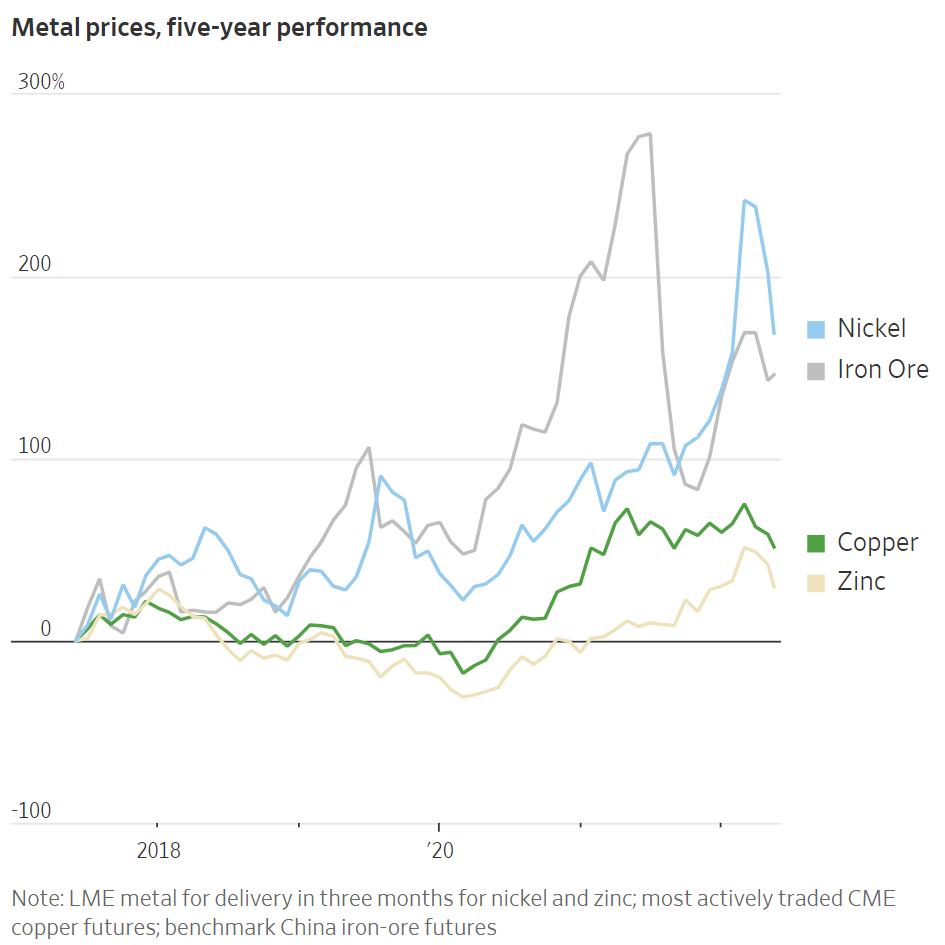

Wall Street Journal: Mining Firms’ Cautious Spending Threatens Shift to Green Energy – The long and the short of it: metals prices are up, but mining companies aren’t spending. The figure below shows the five-year performance of metals such as nickel, iron ore, copper and zinc. Copper and iron ore prices have increased 40% over the last two years, in turn driving up prices for batteries, solar panels and wind turbines. Of course, we’ve all heard, and you’ve seen in this column coverage of cobalt and lithium price increase and availability as well.

Source: Dow Jones Market Data

The Journal notes that the companies’ restraint could keep supplies tight and magnify shortages of raw materials such as copper and zinc that are critical for the transition away from fossil fuels. Project spending by 10 companies will be about US$40 billion this year and next but below the 2012 high of US$80 billion. Unless spending on new mines increases, many analysts see a more severe brake on clean-energy progress.

Washington Post: Ship Pollution Is Rising as the U.S. Waits for World Leaders to Act – This article details environmentalists’ efforts to push the Biden Administration to stop waiting around for the IMO to take stronger action on shipping-derived GHG emissions and instead act on its own. These groups point to the EU as an example citing the EU Commission’s plan to regulate these emissions under its Emission Trading System (ETS) which it proposed under its Fit for 55 program last year.

Environmentalists and others say that by waiting for the international agency to act, the United States is ceding the authority it has to lower shipping emissions on its own and bolstering the industry’s arguments for delay. They want Biden to set specific targets for all ships calling on American ports to zero out their GHG emissions, as well as new rules requiring ships to turn off their engines and plug into the power grid while docked. One group, the Moving Forward Network, is pushing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to require all new marine engines to stop emitting CO2 by 2035.

EPA is unlikely to do much. First, its power is limited as it does not have authority over most vessels docked in U.S. ports. The article notes it can regulate only domestic ships, which make up a small fraction of the global fleet. The Agency is focused on the reducing emissions from vehicles. Another problem: Congressional legislation will be required and that’s not likely to happen in the current political environment. The Biden Administration could facilitate a reduction in ship fuel consumption by lowering travel speeds in federal waters and offering incentives for the adoption of zero-emission technologies.

Ship emissions may be a small part of transport GHG emissions, but they are growing prodigiously. A case in point cited in the article: According to Southern California air-quality regulators, ship traffic is on pace to be the top source of smog-causing pollutants by 2028. But because of the pandemic, this timeline is in flux. If the region continues to experience massive port congestion, ships could become the area’s dominant polluters as early as 2024. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) is now considering tightening standards for vessels.

Tammy Klein is a consultant and strategic advisor providing market and policy intelligence and analysis on transport energy to the auto and oil industries, alternative fuels industries, governments and NGOs. She writes and advises on petroleum fuels, biofuels and other alternative fuels, and fuels policy, market and technology issues.