In France, we love bureaucratic norms, we just create new ones and never suppress old ones, some date back to Napoleon.

In 2016, the Ministry of Ecology decided driving would become conditional, in case of an acute pollution event or in densely populated urban areas, aka Low Emissions Zones (French acronym: ZFE). All vehicles, light or heavy-duty, would be required to show a pass on the windshield, a sticker called “Crit’Air”. The good news, getting the sticker is free of charge. Send a copy of your registration document and you receive your sticker by return mail. More than 22 million stickers have been sent so far.

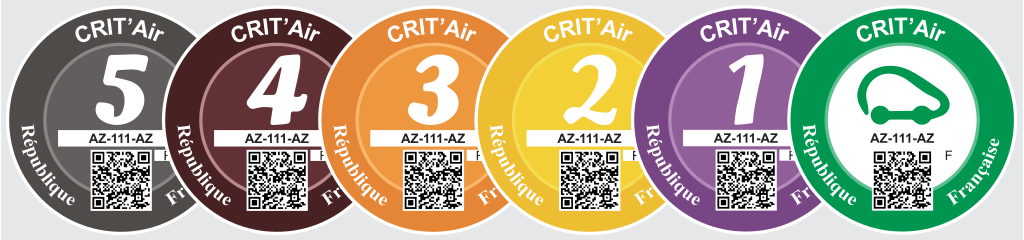

The sticker states which Euro emissions norm the engine respects, and comes in six grades, 0 to 5, color-coded, from 0-green (Electric Vehicles, EV, and hydrogen-powered vehicles, 2035 EU norm) to 5-black (Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles, ICEV, diesel-powered, respecting the Euro 2 norm, sold new between 1997 and 2000). Cars that got on the roads before 1996 (engines respecting Euro 1 norm or no norm at all) are not eligible to any sticker. And the grade-color is the condition to be able to drive, and the chokehold is set to tighten as time goes by.

So far, so good. As engine technology has significantly progressed in the last 20 years in terms of pollutant emissions, NOx and particulates most particularly, it makes sense to curb pollution in dense urban areas by restricting the access to cleaner vehicles, the level of cleanliness being dictated by the severity of the air quality problems. And there is a serious health issue with poor air quality, France is regularly condemned by the European Commission for not meeting basic standards, and not doing enough to get there.

The next logical step to keep on improving air quality in dense urban areas is to make access more and more restricted. By 2025, in less than 3 years from now, the law should transform 45 French urban areas as ZFEs, concerning 44% of the population, de facto banning cars belonging to the Crit’Air categories 3 and above, gasoline-powered cars that were sold before 2005, Euro 2 & 3, diesel-powered cars sold before 2010, Euro 4.

It is not a good thing to be driving a diesel car these days. “Exiled from main street” motorists, 2025 version, drive a massive 75% of the 40 million-strong and highly-dieselized car pool, bearing in mind 38% of the poorer citizens are owning Crit’Air 4 and 5 vehicles. Not omitting that many of those have been rejected from city centers to exurbia by housing cost, but are still obliged to come and work in the same cities they have been pushed away from, by car, as public transport does not reach that far in the countryside.

In a nation where equality is second in the national motto, behind freedom and before mutual support, we have a clear case of discrimination against the vast majority of motorists, the less wealthy ones. Sure, solutions exist: more, and improved, public transport, modal switch (jargon for car to public transport) parking facilities at the ZFE border, infrastructures that will not appear overnight. The magic solution is the much-publicized “cash-for-clunkers” program, a favorite of carmakers. Obviously targeting the switch from ICEV to EV. Not so easy, though: the typical budget for car replacement that can afford the future banned motorists is typically between 5,000 and 10,000 Euros. With a low resale value of the presently owned ICEV, it would take quite a public support to meet the average sales price of a new EV, beyond 25,000 Euros for a similar size and with the requested range for home-to-work and back. Noteworthy that a typical second-hand EV on the market today shows a limited range that does not meet the exurban driver’s requirements. Obviously the early adopters of EV ownership were wealthy urban dwellers.

So, it seems we are again facing a cart-in-front-of-the-oxen situation. We already faced technical feasibility issues, with the supply of renewable electricity, in volume and price, and of battery materials, with the lack of recharging infrastructure, and this example shows road transport transition towards zero emission is also a matter of social justice, not a small problem in our societies today. The combination of these issues, in front of the willingness to move (too?) fast, makes more and more people, as John Eichberger in a brilliant recent podcast on Tammy’s website, question the credibility of EV adoption in the timeframe that is proposed.

Philippe Marchand is a Bioenergy Steering Committee Member of the European Technology and Innovation Platform (ETIP).