A cardinal law of Economy is that demand and price are related, a softening of this rule is called elasticity, explaining that some goods and services will not follow the iron rule: in other terms, a significant increase in price may not induce a real drop in demand. There is obviously a limit to elasticity. In previous centuries, when food made up most of anyone’s budget, crops shortages created famine riots. In the recent past in France, an increase in car fuel prices, spurred by a decent climate improvement regulation and a carbon tax gradual increase, was the final straw for some middle-income citizens, laden with structural, also called constrained, expenses, and ended up in a winter of discontent, labeled Yellow Vests insurrection.

Little has been published of the real impact on citizens of a “serious” fight against climate change, such as the European Green Deal (EGD). This is possibly because it may represent a political bomb in our fragile democratic regimes, whether the impact is financial, putting in peril the long-fought battle of the twentieth century for an ever-improved standard and lower cost of living, or, worse maybe, in a reduction in the way of life, considered today a due. This is especially true in the EU, where consumer protection has been at the heart of the Commission approach for a long time, even when it was at the expense of industry well-being. But times, they are a-changing, and the EU Commission now supports the very ambitious EGD to reach net zero carbon in 2050, which can only:

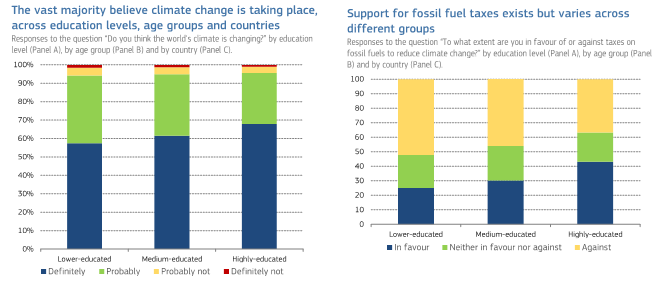

Without huge public support for the EGD, it is possible that EU Member States will reluctantly engage in huge efforts and their bitter consequences. As illustrated in the 2019 edition of the European Employment and Social Development in Europe (ESDE), conflicting messages come from the citizens.

Education-level, which can reasonably be considered as a proxy for income-level, does not play a role in the acceptance that climate change is happening (left-hand graph below), but does play a role in the validation of solutions, here exemplified by the role fossil fuel taxation could play (right-hand graph below), hinting that citizens know quite well how governments address challenges — more taxes — and the unavoidable consequence thereof, additional poverty. And, like in the proverbial story of the frog plunged in gradually warming water, the consequences of climate change, how dramatic they may be in the long term, such as a 4 % reduction in Gross Domestic Product in Southern Europe, are too slow to materialize in everyday life to counter-balance the fear of a drift towards poverty.

If 50 million people in the EU, very likely from the first and the early part of the second deciles of revenues, today suffer from energy poverty, how many more will join if the average energy bill increases by 23-28 % between 2015 and 2030 (source: EU Commission 2020 impact assessment of the document “Stepping up Europe’s 2030 climate ambition”), if food cost raises by 30 % (believed to be the premium paid for organic food vs conventional, the social impact assessment of the EU Farm-to-Fork and Biodiversity strategies not being public), not omitting transport cost, which can only increase, for which no social impact assessment is available? Knowing quite well that lower-income citizens are the least assured to benefit from any growth, green or not, as inequalities relentlessly rise.

An obvious solution, becoming mainstream (as in 2019 ESDE, op.cit.), is that social protection or welfare systems will support lower-incomes, cancelling out the extra cost of climate change solutions, and the onus is put on Member States to adopt the right measures for a just and socially balanced transition to climate neutrality. Fine, but the moneys involved are formidable: a rough estimate, in the absence of peer-reviewed impact assessments, hints that increases in energy, food and transport alone could amount to 5-10 % of the EU GDP, close to what taxes on revenues bring to nations coffers. If half of the EU citizens cannot afford this increase, that could be labeled climate transition poverty. It is left to the other half to compensate every year. In France, where less than 50% of households pay income tax on their revenues, including many that took part in the Yellow Vests movement, the burden could nearly double, which will likely create, a minima, social unrest, revolutions have been started for less.

Conclusion: Any green deal serious about climate transition, must not only be about innovation and investment, but also address recurring expenses, to make sure just and socially balanced regulations do not end up in a social upheaval. The sooner this is explained to the citizens, the sooner citizens will adopt behaviors self-helping towards climate neutrality, towards a greener way of life.